From an architect designing a building to a biologist trying to dissect the molecular causes of a disease, it is crucial to understand the relationship between structure and function. At the scale of a building, this relationship is easy enough to understand. The number and types of rooms will be different for an office building and a single-family home. But for structural biologists, the objects of interest—viruses, proteins, or DNA, for example—are almost unimaginably small. And they are not static!

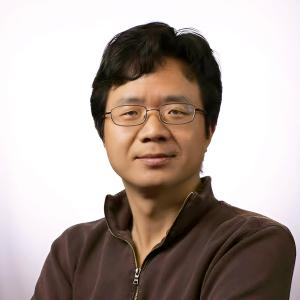

“Until recently, the main technique to determine the structure of a molecule was X-ray crystallography,” said Wen Jiang, Dorothy Foehr Huck and J. Lloyd Huck Chair in Structural Biology and professor of biochemistry and molecular biology. “Molecules were first crystallized, aligning them into a static repeating pattern. Hitting these crystals with X-rays creates a diffraction pattern that could be used to reconstruct the 3D structure of the molecule. But not all molecules are amenable to crystallization, and, more importantly, we know that the molecules aren’t static in the cell as in crystals. They move and can even change shapes to perform their tasks.”

Jiang is a structural biologist and is the faculty director of the Cryo-Electron Microscopy Core Facility in Penn State’s Huck Institutes for the Life Sciences. He explained that with instruments like the ThermoFisher Titan Krios—the cryo-EM microscope housed in the core facility—biologists can reconstruct atomic-scale 3D structures of molecules without crystallization. Now, the hurdle to overcome is the massive amount of data the instrument can produce and separating the signal from the noise in the images. This is where AI comes in.

“With cryo-EM, the sample is prepared in an aqueous solution, and the molecules are not fixed in a specific orientation like they are with X-ray crystallography,” said Jiang. “This means that the microscope will ‘see’ the molecules from all different, but unknown angles, and as the molecules can form different structures, they might not all be uniform. It’s kind of like trying to figure out what a human looks like if all you had were faint snapshots of people dancing taken from multiple different viewpoints.”

The image processing pipeline to determine molecular “dancing” now relies heavily on deep learning methods using artificial neural networks. These techniques help the researchers isolate the signal from the noise in the images and understand how images of molecules in different orientations and structures relate to one another.

“The images we get from cryo-EM are two-dimensional projections captured by electrons passing through the sample, which is a heterogeneous mixture of molecules at different angles and in different poses,” said Jiang. “The deep learning models are fed this data and iteratively ‘learn’ how to reconstruct the 3D structure in a way that is still very much a black box.”

One area of interest in Jiang’s lab is the structure of amyloid proteins that can form plaques that are related to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. These proteins form helical structures which are particularly difficult to reconstruct, and they can form different structures in different patients. Jiang’s graduate student, Daoyi Li, who earned a doctoral degree at Purdue University where Jiang was a faculty member before joining Penn State, developed an AI approach to help understand these structures that works similarly to a large-language model like ChatGPT.

“We collected cryo-EM images of amyloid fibrils,” Jiang said. “The model treats the helical structures as a series of short segments, the way ChatGPT treats sentences of text. This allows us to identify ‘words’ in the structures and start to understand how they might relate to each other to provide context that could help determine their structures, giving us clues to how and why the plaques form.”

As faculty director of the cryo-EM facility, Jiang works with faculty from across campus and gets to see first-hand how interdisciplinary approaches are helping to push the field forward. He emphasized that Penn State is one of only a few universities with aberration-corrected cryo-EM instrumentation and expert staff to help researchers find new and innovative ways to use it.

“Penn State was prescient to invest in this technology and continues to do so,” Jiang said. “We are in the process of installing a focused ion beam instrument that will help us to start imaging slices of whole cells, so we can start to see structures in their native context. We are always looking to improve our methods, from sample preparation to final data processing, and AI methods are a big part of that. There are still studies that use traditional methods for image analysis, but AI is becoming the dominant model. It’s improving the capability, speed, and efficiency that we can do things.”

Editor's Note: This story is part of a larger feature about artificial intelligence developed for the Winter 2026 issue of the Eberly College of Science Science Journal.