Uncovering Galaxies Buried in Dust at the Cosmic Dawn

Two previously invisible galaxies completely hidden by clouds of cosmic gas and dust have been discovered. While investigating new data of young, extremely distant galaxies observed with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, astronomers noticed unexpected emissions coming from seemingly empty regions of space. The team discovered that the radiation was emitted billions of years ago and came from two dust-enshrouded galaxies.

“Studying the most distant galaxies at the cosmic dawn is one of the ultimate frontiers in astronomy,” said Yuexing Li, associate professor of astronomy and astrophysics. “It is essential for our understanding of the formation of stars and interstellar medium in the early universe, which impacts the formation and evolution of galaxies at the present day such as our own Milky Way.”

A key goal of scientists is to identify all the galaxies in the first billion years of cosmic history and to measure the rate at which the galaxies were growing by forming new stars. It was unexpected to find such dust-enshrouded galaxies this early, less than 1 billion years after the big bang. The discovery suggests that the current census of early galaxy formation is most likely incomplete and would call for deeper, blind surveys.

The Pathway for Producing Ethylene

By Sam Sholtis

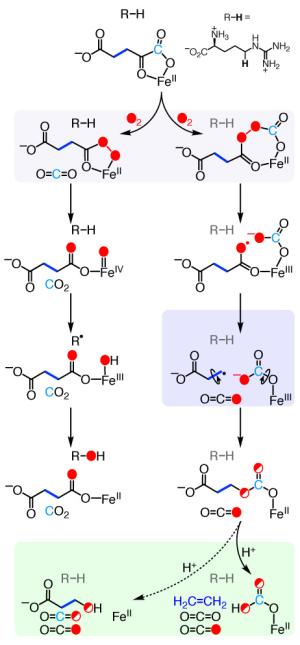

New research lays out the chemical steps used by a naturally occurring enzyme to convert a common chemical compound into ethylene—a plant hormone important for fruit ripening and an industrial chemical used in the production of plastics and textiles.

“Currently, petroleum is our main source of ethylene for these uses,” said Rachelle Copeland, a recent Ph.D. graduate. “However, plants and some microbes produce ethylene naturally. Understanding the step-by-step chemical process used by these plants and microbes could help us move away from petroleum-based ethylene production.

The aptly named “ethylene-forming enzyme (EFE)” is able to transform a common chemical compound—2-oxoglutarate—into ethylene.

“Our lab group has been studying enzymes related to EFE for close to 20 years,” said Carsten Krebs, professor of chemistry and of biochemistry and molecular biology. “EFE is unique amongst this family of enzymes because it breaks down 2-oxoglutarate in two different ways. The first is well characterized, but the second, the one that produces ethylene, has been a mystery until now.”

“Rachelle designed these experiments to look at the most fundamental aspects of the reaction,” said J. Martin Bollinger Jr., professor of chemistry and of biochemistry and molecular biology. “Where do the individual atoms go? And it maps out an unmistakably clear mechanism.”

Elusive Mergers of Black Holes with Neutron Stars Confirmed

Over the last five years, researchers have identified more than 50 gravitational wave signals— disturbances in the curvature of space-time—from the merging of pairs of black holes and of pairs of neutron stars, but never the two together. Now, an international team has observed two such events just 10 days apart in January 2020 using the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in the U.S. and the Virgo detector in Italy.

“We can now study how many such systems exist in the universe, where they have been formed, and how often they merge,” said postdoctoral researcher Leo Tsukada.

One of the LIGO detectors was temporarily offline during the first event, which would usually make it challenging to detect the event due to background noise.

“GW200105 stands out against the background data and is different from features that we expect from noise, and that’s how we know that this must be a gravitational wave event,” said graduate student Divya Singh.

"Both of these mergers were detected as part of real-time gravitational wave processing conducted by members of the Penn State LIGO group,” said Chad Hanna, associate professor of physics and of astronomy and astrophysics. In both cases, the neutron star was likely swallowed whole by its black hole partner.

Snapshot USA: First-Ever Nationwide Mammal Survey

The results of the first-ever nationwide mammal survey, Snapshot USA, provide the framework to answer a variety of questions about wild animal populations and conservation strategies for threatened species. Until now, there has been no standard way to monitor mammal populations at a national scale.

“Remote-triggered cameras—camera traps—have revolutionized wildlife research, especially for mammals that are too wary to observe directly or only come out at night,” said Sean Giery, Eberly postdoctoral research scholar who participated in the survey. “Now, we can set up motion-triggered cameras for months at a time, learning what animals are present in an area and how abundant they are.”

For two months in fall 2019, a team of more than 150 researchers collected more than 166,000 images of 83 different mammal species at 110 sites located across all 50 states. The data are available online for anyone to use for research.

“The data generated from this immense project are invaluable for answering fundamental questions about wild mammal populations,” said Giery. “But I think the real benefits will come years from now, when we can use these data as a baseline to measure change in the diversity, distribution, and abundance of mammals in the United States.”

Stop the Genetic Presses!

By Sam Sholtis

A bacterial protein helps to stop transcription—the process of making RNA copies of DNA to carry out the functions of the cell—by causing the cellular machinery that transcribes the DNA to pause at the appropriate spots in the genome. The protein, known as NusG, pauses the transcription machinery at specific DNA sequences to facilitate what is called intrinsic termination.

A new study shows that NusG and the related protein NusA together facilitate termination at about 88 percent of the intrinsic terminators in the bacteria Bacillus subtilis.

“Termination of transcription is especially important in bacteria because the genes are packed tightly together along the genome, such that failure to terminate transcription at the right locations could lead to inappropriate gene expression,” said Paul Babitzke, professor of biochemistry and molecular biology.

The research team produced strains of bacteria that lacked NusA, lacked NusG, and lacked both.

“We found that some intrinsic termination sites were dependent on NusA, some on NusG, some on either NusA or NusG, and some required both,” said Zachary F. Mandell, a graduate student and first author of the paper.

Understanding this process expands our basic knowledge of this key cellular function and could eventually aid development of antibiotics that target and disrupt gene regulation in bacteria.

Study Challenges Standard Ideas about Piezoelectricity in Ferroelectric Crystals

By Jamie Oberdick

Many electronic devices, sensors, and actuators rely on piezoelectricity, where a material called a ferroelectric crystal generates an electrical charge under an applied mechanical force.

“Our work provides a theoretical foundation for correlating piezoelectricity to crystal symmetry, crystal orientation, and domain configuration,” said Long-Qing Chen, Hamer Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, professor of engineering science and mechanics, and professor of mathematics.

At a microscopic scale, ferroelectric materials consist of many domains that are known to influence piezoelectricity and can range in size from a few nanometers to as much as millimeters. Conventional belief in the field is that the smaller the domain size, the larger the piezoelectric coefficient.

“Our theory and computation demonstrated that such a conventional view is actually not often correct,” said Bo Wang, postdoctoral scholar in materials science and engineering. “We proposed a theoretical model of domain change under electric fields, we use computation to confirm it, and because of our simulation, we have shown that researchers in the future will have to look inside the crystal.”

This new understanding of the relationship between ferroelectric crystal domain size and piezoelectricity can provide guidance to improve piezoelectric performance of materials.

Staying Home and Limiting Contagion Hubs May Curb COVID-19 Deaths

By Gail McCormick

Using novel techniques in a field of statistics called functional data analysis, an international team of researchers compared the first wave of the COVID-19 epidemic across 20 regions in Italy and identified factors that contributed to mortality. They found that local mobility—how much people moved around their local areas—was strongly associated with COVID mortality.

“We see the effect with a lag, but when people reduced their mobility, we saw fewer COVID-related deaths,” said Francesca Chiaromonte, Lloyd and Dorothy Foehr Huck Chair in Statistics for the Life Sciences. “And we aren’t the only ones to document this, so when we’re told to stay home as a mitigation measure, we should stay home!”

The research team also investigated several demographic, socioeconomic, infrastructural, and environmental factors.

“What reduces mortality may not be so much having big fancy hospitals with lots of ICU beds, but rather having good access to primary care doctors,” said Chiaromonte. “In fact, having big hospitals may have backfired because they acted as contagion hubs.”

These results could inform local decision-making, for example encouraging short- and medium-term investments to boost primary health care and to limit contacts in contagion hubs by encouraging pods in schools and workplaces and segmenting sections in hospitals.