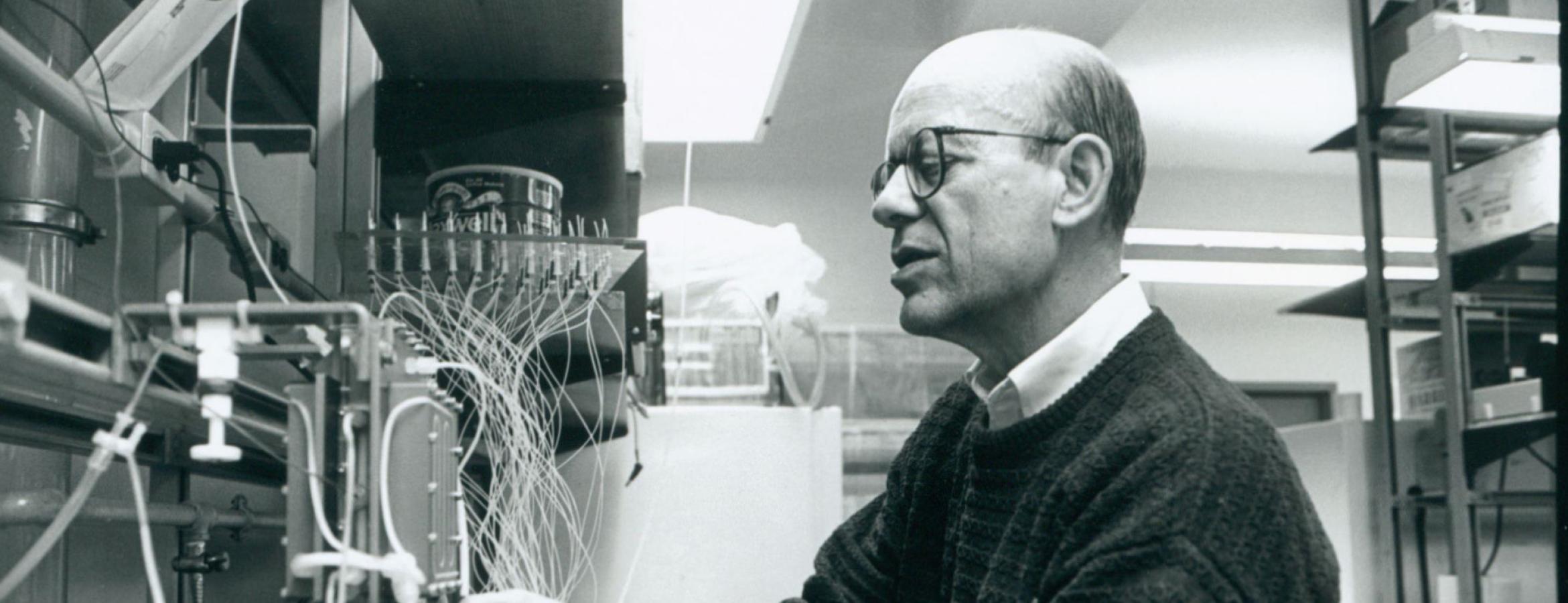

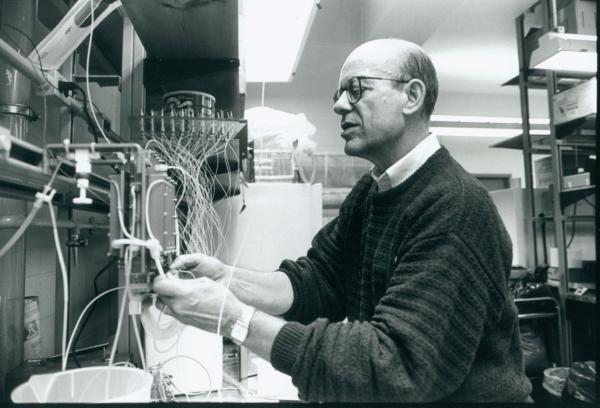

The Eberly College of Science mourns the loss of Wesley Hymer, professor of biochemistry, who died on May 4 at the age of 89. Over his 35 years on the faculty at Penn State, he made important contributions to the understanding of pituitary hormones and was internationally recognized for his pioneering research of living cells in space.

“Wes was a dedicated researcher and educator who was always full of energy and enthusiasm,” said Ross Hardison, professor emeritus of biochemistry and molecular biology at Penn State. “He had a long and productive career conducting research on the biochemical and cellular mechanisms by which pituitary hormones regulate growth and differentiation in mammalian tissues. He was the first person I heard talking about muscle loss and other negative physiological impacts of space travel and weightlessness. He ran an early, innovative research program studying these issues, including experiments conducted on space shuttle flights.”

A native of Wisconsin, Hymer earned bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degrees at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and then served as a postdoctoral fellow and staff fellow at the National Institutes of Health’s National Cancer Institute. Hymer joined the faculty at Penn State in 1965 and retired with emeritus status in 2000.

Hymer’s research largely focused on pituitary glands and two of the hormones they produce, prolactin and growth hormone. This included topics such as the synthesis, processing, and secretion of mammalian pituitary hormones, isolation of bioactive hormone forms, and pituitary-cell separation.

“When I came to Penn State in 1966 as a graduate student in the Department of Biology, Wes was a new assistant professor from the NIH,” said Andrea Mastro, professor emeritus of microbiology and cell biology at Penn State and one of Hymer’s first graduate students. “He was carrying out cell and tissue culture in his laboratory, and these were exciting new areas.”

In 1983, Hymer was the principal investigator on the first experiment conducted aboard the space shuttle in which live cells were processed by a separation technique called electrophoresis. Over the next 10 years, he led five more cell studies that were conducted in space, including two in the Cosmos biosatellite series, a joint Russian-U.S. effort, and one that resulted as a collaboration with Japanese researchers. Hymer's space experiments with living cells developed conclusive evidence that the hormone output and activity of pituitary-gland cells is adversely affected by the lack of gravity in space, which may contribute to the bone loss of astronauts in space.

“We carried out some interesting collaborations with scientists from the Soviet Union,” said Mastro, who Hymer invited to participate in his work with NASA several years after she returned to Penn State as a faculty member. “Our travel included several weeks in Moscow along with some other American scientists. This led to long-term collaborations and to some of the Russian scientists visiting our labs.”

In 1987, Hymer was awarded $5 million from the NASA Centers for the Commercial Development of Space program to launch the Center for Cell Research (CCR) at Penn State. For several years, the center focused on developing commercial biomedical and biotechnical experiments based on the idea that space could be used as a testbed for the development of new medicines. This resulted in experiments with Genentech, Merck, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Merocel Corp., Boehringer Ingelheim, Clontech Laboratories, the Space Dermatology Foundation, and Genetics Institute. By 1993, when NASA changed its focus and retired the Centers for the Commercial Development of Space program, the CCR had flown commercial experiments aboard four space shuttle missions and three sounding-rocket flights, developed four patented products, and renewed NASA's interest in electrophoresis as a space-processing technique.

In 1990, Hymer received a Faculty Scholar Medal from Penn State for his achievements. In a nomination letter for the award, Daniel Tershak, then associate professor of microbiology and molecular biology at Penn State, said, “W.C. Hymer is a creative scientist with the unique ability to identify important problems and develop in-depth, multidisciplinary, innovative approaches to their solutions. He also has the rare combination of personality, attitude and vision to attract high quality scientists into collaborative projects. Hymer has given [Penn State] national and international recognition, put [Penn State] at the center of an extensive network of scientists, and structured a firm path toward ambitious goals for [Penn State].”

Penn State is now known as a Space Grant institution largely thanks to Hymer, who helped develop the successful proposal that resulted in Penn State participation in NASA's Space Grant College program in 1989. The program continues to support student research in the space sciences as well as other space-related activities.

“One of the lasting impacts of this research program was the establishment of the NASA-supported Pennsylvania Space Grant Consortium, which is still active today, supporting students pursuing careers in science, mathematics, engineering, and technology while also providing public service education,” Hardison said.

Hymer also was a devoted educator and mentor. Later in his career, Hymer taught a popular course on the human body for nonscience majors that attracted several hundred students each term.

“He was a very dedicated faculty member and mentor, and he took teaching in the classroom and in the laboratory very seriously,” Mastro said. “He was very hands on; he showed me, not just told me, how to carry out experiments. Wes was also very supportive of me, nominating me for several awards and helping me expand my professional network. There were not any women faculty in the department at the time, and he arranged for me to spend a summer with a woman scientist at NIH. Because I didn’t have a car, Wes and his wife, Marge, and the kids drove me to Washington. He was a great teacher and collaborator, and I was fortunate to meet Wes just at the right time in our careers.”

In his retirement, Hymer continued his research with collaborator William Kraemer, who at one point served as director of research in the Center for Sports Medicine and associate director of the Center for Cell Research at Penn State. Their longstanding collaboration resulted in more than 26 research papers over the years, and they were discussing a new project a few days before Hymer's passing.

“Wes and I first met during my time as a professor of applied physiology at Penn State, where our shared interest in endocrinology—particularly growth hormone and the anterior pituitary—sparked a collaboration that would last for over 30 years,” said Kraemer, who retired as professor of human sciences at the Ohio State University in 2022. “He was a brilliant scientist and a great friend and mentor. Even as my career later took me to other institutions, including my final post at the Ohio State University, our work continued, producing over two dozen studies that bridged molecular biology and human performance.”